Thaddeus S. C. Lowe |

Thaddeus S. C. Lowe - The War Years

|

Thaddeus Lowe was a man of that breed whose courage and vision sparked America's tremendous progress and growth during the 19th Century. He was an inventor, an entrepreneur, a visionary and a determined risk-taker. He put his money where his mouth was. When he saw a window of opportunity he would go for it, despite the detractors who told him it couldn't be done. He pioneered systems that were a first of it's kind, and may well have been one of those early genius producers who changed the coarse of history with his development of gas generators, communications systems, a system of lighting safe to use near flammable gases, artificial ice, refrigerated ships, and aeronautics which were a precursor to our U.S.Air Force. Lowe volunteered his services to President Abraham Lincoln and became the chief Ballonist for the Union Army during the Civil War. This page is dedicated to some of the events that led up to that volunteering, and the resulting stories that displayed the importance of Lowe's reconnaissance in support of the Union. The stories below are taken from the book Above the Civil War by Eugene B. Block, and donated to this webmaster for the writing of this piece by Brian Marcroft. |

|

Cable Dispatch to Abraham Lincoln from Balloon On

June 17, in 1861, on the grounds of the Columbia Armory in Washington, the

specially equipped Enterprise ascended on tethers to a height of 500 feet,

carrying Lowe and representatives of the American Telegraph Company. Using

telegraph equipment aboard the ship and cables that ran along one of the

rigging wires to the ground and from there to the War Department and the

White House, Lowe sent the world's first telegraphic transmission from the

air: Balloon

Enterprise, To the President of the United States Sir: This point of observation commands an area nearly fifty miles in diameter. The city, with its girdle of encampments, presents a superb scene. I take great pleasure in sending you this first dispatch ever telegraphed from an aerial station, and in acknowledging my indebtedness to your encouragement for the opportunity of demonstrating the availability of the science of aeronautics in the military service of this country. yours respectfully, T.S.C. Lowe The ingenuity of this demonstration was not lost on the commander in chief. Lowe had firmly cemented his relationship with Lincoln. For the rest of the evening of the 17th, the Enterprise was moored on the South Lawn of the White House, while Lowe remained as a guest in the executive mansion. Source for this dispatch is from this Website |

In a solemn mood, his face lined by many cares, President Lincoln sat at his desk on a day late in July, 1861. Through a window came ominous distant rumblings of artillery fire, far away in Virginia beyond the Potomac. The Union Army had just suffered humiliating defeat in the first battle of Bull Run. (First Manassas)

A tap at the door interrupted the President's thoughts and an aide entered, announcing that "a Professor Lowe is here to see you.'"

"Show him

in right away, Abraham Lincoln directed. I've sent for him."

Into the executive chamber of the White House stepped a

29-year-old stranger, slightly more than six feet tall, heavily built and broad

shouldered, with a bush black mustache and thick, neatly parted dark hair.

His blue eyes were deep and penetrating, and there was an intelligent, eager

look on his face. He wore high boots, a long black coat, and a plaid vest

of the time. In his hand he carried a large, black, broad-brimmed hat.

"I've been thinking, the President began, that our

defeat at Bull Run might have been averted if someone in a balloon could have

observed the movements of the Confederate forces."

Thaddeus Lowe nodded agreement.

After a slight pause, Lincoln recalled a telegram he had received more than a month before from Lowe -- the first communication of its kind ever tapped out from a balloon in space. It was a message sent by the aeronaut from a height of 500 feet above the grounds of the Columbian Armory in Washington. In it, Lowe had offered further demonstration of the value of aerial reconnaissance to the military service of his country.

"I am now ready to accept your offer, the President finally said. Can you proceed at once?"

Thus started 2 years of aerial reconnaissance by T. Lowe and his special band of men in support of the Union Army. Though they worked tirelessly for the Army, providing incredible support and assistance, the Balloon Corps was never officially "in the Army". Lowe had requested many times to be made a military officer, and thereby provide he and his men the security of being part the military code of justice. During war, when a soldier is captured, he is a Prisoner of War, and is given the protection and succor under law that is provided for soldiers. However, if one is a private citizen, he may be shot on the spot for treason by his capturing force. The Corps, many a time in it's flights found themselves over enemy lines, and being the target of many cannon and rifle artillery worried that they could be shot down, captured, and put to death.

Thaddeus S. C. Lowe |

Lowe had been experimenting with ballooning for quite some time before approaching Lincoln. He had gained fame and notoriety by traversing approximately 900 miles from Cincinnati, Ohio to Charleston, South Carolina. A feat never before accomplished, and newsworthy throughout the land. At the time, Lowe was not motivated or concerned with politics and arranged his flight on April 20, 1961 - about a week after southern confederates fired upon and took Ft. Sumter in that same city. The Civil War between the North and the South had begun.. Lowe, a Yankee from Ohio, was descending into southern territory, and was met with great suspicion. Men held him at gun point, he was apprehended, and only the newspapers in his basket from Cincinnati declaring the event and naming him by name offered him a reprieve and release.

There were other men who were experimenting with balloons. The first balloon bought for American military use was by John Wise of Pennsylvania. He tried to get his balloon to Washington before the first battle of Manassas, but he was too late and he had too many problems, and finally abandoned his efforts. The first really effective balloon observation on behalf of an army came from John LaMountain of New York. He had gained fame and notoriety by sailing 1,100 miles in less than 20 hours in a balloon.

Both Lowe and LaMountain were hired to be balloonists for the Army. They were each paid $10 per day. But it became Lowe's responsibility after being hired by Lincoln, to organize the Balloon Corps. The professor, though much younger and less experienced, became the dominant figure in the war's aerial operations. LaMountain and Wise, along with others, eventually worked under Lowe's command.

Most of Lowe's experience was during the Peninsular Campaign when General George B. McClellan was commanding officer. It took McClellan awhile to realize the value of the balloons (as was the case with all the other Generals he worked with). Once he saw the value, Lowe was sent aloft many, many, many times over a period of two years, often with Generals going up with him. It is rumored that even Lincoln went up with him once.

|

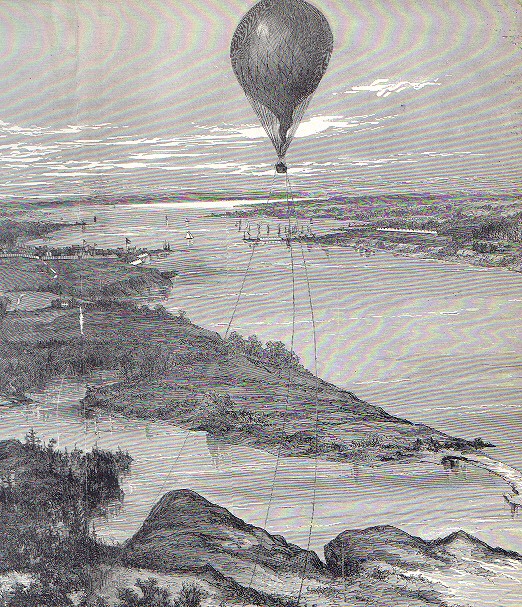

Lowe was once sent aloft near Union General Joseph Hooker's headquarters in the Washington area to verify reports of enemy gun emplacements. He reported a line of rebel camps skirting the river for several miles and could see heavy guns, including one he recognized as having been captured from Union troops during the Manassas engagement. The Balloon Corps was credited with repeatedly thwarting military coups, especially those of the wily General P.G.T. Beauregard, causing that astute officer great frustration and chagrin. The most careful use of trees and shrubbery as cover failed to conceal Confederate installations from the eyes of balloonists surveying wide sweeps of enemy terrain from heights usually of 1000 feet.

However accurate the information provided by the balloonists' observations, it was of no military value until available to the men on the ground who needed it. Promptness and accuracy of communication were essential. To speed up messages Lowe devised a system of special codes utilizing numbers and letters separately or in combination. This was in addition to the wire telegraph he installed to make electrical transmission. But this method was sometimes unreliable because of the vulnerable wire and the possible failures of the primitive telegraphic equipment then in use.

Prior to his balloon construction and exploits in the air, Lowe would lecture to large audiences explaining scientific principles and demonstrating them with the aid of a small portable laboratory which he had purchased with his savings. After accumulating sufficient funds from his lectures he settled in New York where he enrolled in a school that provided advanced courses in chemistry and other fields of science. For a time he turned to medicine, which had interested him since the childhood days when his grandmother had discoursed on home remedies and her simple smattering knowledge of diseases. It is unlikely that he ever practiced as a physician. Probably he abandoned the medical studies because of his far greater interest in ballooning.

|

Leontine A. Lowe |

In one New York audience one evening there sat a 19-year-old French girl, brilliant and beautiful, who lingered on his every word. The lecture over, she arranged for an introduction in the hotel where both were staying. She was Leontine Augustine Gachon, a native of Paris. A member of the bodyguard of King Luis Philippe, her father fled France after the king's overthrow and brought his family to America with a party of royalist refugees. The girl had been seeking a stage career when she chanced to attend Lowe's lecture. They promptly fell in love and were married a week later by a justice of the peace in the parlor of the little hotel where they met. It was February 14, 1855, and Lowe was not yet 23 years old.

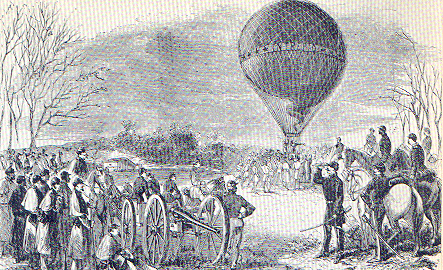

Only two months after assuming his command, Thaddeus Lowe provided a dramatic new chapter in military history by actually directing artillery fire from the air during the progress of a battle, enabling gunners on the ground to shell an enemy they could not see.

It was September, 1861, at a time when Union forces were expecting an attack. Lowe was directed to ascend above Fort Corcoran in Virginia on the south bank of the Potomac and he soon reported the presence of enemy guns poised more than three miles away. Details were telegraphed from the balloon to the nearest Union commander, including the important fact that Falls Church, Virginia, was being shelled by the rebels.

From aloft Lowe flashed the results of successive volleys until the Union gunners had corrected their ranges and were hitting the unseen enemy's positions. He continued to give the ground forces a shot-by-shot account of the battle, the first such operation ever recorded.

During this same period Lowe experienced one of his many narrow escapes from death or capture. His wife, though young and not too robust at this time, played a courageous role. The Corps had been called on to verify reports that the rebels were marching on Washington. These rumors were creating widespread alarm which subsided only after Lowe, by aerial observations, proved the fears unfounded.

He had ascended at sunrise in a captive balloon from a point dangerously close to enemy lines. A stiff wind veered him slightly over rebel territory and after hastily completing his observations, he waited a short time until he felt that a change in air currents would permit him to land safely among his own forces. He was still a considerable distance aloft when Union troops opened fire, suspecting that he was a Confederate who had stolen one of Lowe's balloons.

Despite the bullets, he dropped still lower until he heard the shouts of angry soldiers demanding him to "show your colors" but Lowe had no flag with him. He knew that if he continued downward he would be in danger of being riddled and therefore decided to rise again. However, a change in the wind sent him again over enemy lines and he had no recourse but to come down on a plantation in a rebel-held area, a considerable distance from Union troops. In landing, he sustained a severe ankle injury and the balloon was badly torn.

In his predicament and suffering severe pain, he decided to hide in a thicket until nightfall. He did not know that his wife, who had been watching all the while, had seen him fall behind enemy lines. First she ran to headquarters of the 31st New York Volunteers, which dispatched a group of scouts to locate the aeronaut. Accompanied by Mrs. Lowe, they found him a short time later and it was decided that some of the party would remain at his side until evening, when efforts would be made to bring him out under cover of darkness.

There was further consultation with Mrs. Lowe and she evolved a bold means of rescue despite possible risk of her life. At her own suggestion, she returned with several of the scouts to the quarters of the New York Volunteers. There a horse was harnessed to an old covered wagon. After dark, Leontine Lowe donned male attire provided by men at the camp and was driven into enemy terrain to the place where her injured husband lay hidden. He was helped into the wagon and covered by the folds of the balloon, now completely collapsed. The group then drove out of the woods and back into Union territory, discerning in the darkness the dim outlines of several Confederate soldiers, unaware of what was taking place.

|

|

|

At one point in the War, General McClellan faced the stupendous task of moving an army of 125,000 men and all its equipment more than 200 miles. With them were 21,500 horses, 44 batteries, a number of war balloons, ambulances and other essentials. Four hundred steamers and sailing vessels were needed to transport them to the peninsula**

|

|

**In 1962, Major General George B. McClellan, commander of the Union forces, devised a simple plan to end the Confederate rebellion against the United States. He would take the Army of the Potomac, sail it south to the peninsula between the York and James Rivers in Virginia, and rapidly march on to Richmond - the capital of the Confederacy. There he would fight a decisive battle, capture the city and end the war. The campaign, sadly, did not go as planned, and thus the war dragged on for three more bloody years. More info may be seen at http://www.peninsulacampaign.org/ |

McClellan called on Lowe and his Balloon Corps to carry on almost continuous

aerial reconnaissance. This was not only to observe and guide the Union

forces in their progress but also to report any unexpected enemy threat that

might overtake them while they were unprepared for combat. Balloons went

up day and night and were shifted rapidly from one locality to another, with

Lowe reporting frequently to McClellan.

It should be noted here that many of Lincoln's

Generals couldn't match the cunning and prowess of the Confederate

Generals. There was simply no contest, despite the Union Army having more

provisions, supplies and at least double the numbers of men. The cream of

the crop that came out of West Point, VA (which trained military men that knew

each other as classmates, but later fought each other in the War) was largely

under Confederate command. George McClellan, though popular with his men,

was not a good military achiever, and often would avoid battle and opportunity

to take the advantage for fear that he wasn't ready. Lincoln many times

sent dispatches urging the General to move and take action. Lincoln even

had to resort to personal visits to the battle headquarters to order the General

to do something. Lincoln finally dismissed McClellan of his command in

pursuit of a better commander who could get the job done. He went through

several commanders before finally discovering one Ulysses S. Grant. Surely

the many ascents of Thaddeus Lowe and the Corps giving advantage in battle to

McClellan's Union Army tipped the scales making successful campaigns despite the

incompetence of the head General. Most probably, had Lowe not supported

the Army, many more Union failures would have occurred in battle in this part of

the War. Lowe quit the Army before Grant came to power. Lowe's

departure was the result of personal discouragement caused by junior military

officers put in charge of Lowe who jealously wanted to steer the course of

Lowe's command by telling him what to do when they had little or no

experience. In most journals, books, accounts of the war presented

by historians, little is said of Lowe and his Balloon Corps. Had he been

able to remain under Grant's command, chances are, combined with his expert

reconnaissance abilities, and the superior abilities of Grant - the defeat of

the South and the end of the Civil War may have come sooner than 1865. --

Webmaster / Editor

_______

As Lowe's services continued through the succeeding engagements persistent efforts buy the Confederates to shoot down his balloons by artillery fire sometimes caused him unexpected difficulties. The hazard not only raised problems of morale among his aeronauts but also involved him on one occasion with a high officer of the ground forces.

Early in May 1862, during fighting in the vicinity of Yorktown he was summoned to the headquarters of General George Stoneman, commander of the cavalry, who was as mindful of the 10,000 horses in his charge as he was of their riders. "Your balloons are drawing enemy fire over all of my fine horses," Stoneman declared angrily.

Lowe stood up to the General. "My balloons are fully a mile away from your horses," Lowe retorted. "How can shots fired at us endanger your cavalry?"

"I'll tell you how," Stoneman snapped. "Each time the rebels fire their big guns at your balloons, every horse in my outfit humps up his back."

Lowe explained that he could not be held responsible for the effect on the animals and there the episode ended, the General still irate and Lowe indignant. Throughout the day the enemy kept up an intermittent barrage aimed at the balloons.

At dusk Lowe and General S.P. Heintzelman were sitting in front of the General's tent debating the question raised by Stoneman when a 12-inch shell dropped a few yards away, showering them with earth and rock. Fortunately it failed to explode but the narrow escape prompted Lowe to propose that he shift the Corps' observations so as to draw enemy fire in another direction. Heintzelman counseled against an immediate move and his judgment prevailed.

This proved a wise decision, for Lowe was awakened at midnight and ordered to ascend at once to verify reports of a raging fire in Yorktown which the general surmised might be evidence of evacuation. From the air Lowe observed that Confederate barracks, tents and warehouses were intact and any substantial blaze had been extinguished. After signaling this fact he remained aloft throughout the night watching for campfires to appear in the early morning but saw none. Soon after dawn he observed that the entire rebel force had moved out.

Lowe told this to General Heintzelman who later ascended with him, verified the aeronaut's conclusion and telegraphed his report to General McClellan from the air. The two remained aloft and watched the Union forces advancing toward the enemy.

Successes such as this caused Stoneman to change his mind about his horses and to have an interest in the tactical possibilities of the balloons --- a few days later he consented to ascent with Lowe. At a height of 1000 feet they sighted an enemy force concealed near New Bridge, trying to observe Stoneman's movements. Availing himself of his strategic position Stoneman was able from the balloon to direct his battery commanders how to fire at the enemy then beyond their vision. He then moved on to Mechanicsville and routed the rebels encamped there. The general was heard to remark that on this ascent he had seen enough "to be worth many thousands of dollars to the government."

The historic battle of Fair Oaks which began May 31, 1862, was the high point of Lowe's Balloon Corps service.

Some days before the battle General McClellan had decided to change his base from a position on the Pamunkey to one on the James River so that troops and supplies could more readily be transported by water and his communication less exposed to enemy interference. The move, he believed, would increase the chances of a successful attack on Richmond and assistance by gunboats would be more feasible.

After dispatches from Washington had assured McClellan that part of General McDowell's corps would march to his support, the high command unexpectedly refused to heed McClellan's request that the reinforcements be sent by way of the James River and announced that they would come overland instead. This decision placed McClellan in a highly vulnerable position. For strategic reasons he had divided his forces along both sides of the Chickahominy River - half on the Richmond side and the other on the opposite shore guarding the line of supplies while awaiting the promised juncture with McDowell's troops.

With his forces divided, McClellan became faced with a crucial problem when heavy rains and ensuing floods swept away the large bridges which the engineers had built. Before a start could be made on replacing them, word came from Washington that McDowell's men could not be spared because of a possible new thrust by the rebels toward the capital.

Now the need for a new bridge to permit consolidation of McClellan's force became even more urgent. Lowe was ordered to ascend to a height that would command a sufficiently broad view of the area to help determine the best location. However, the new bridge hardly had been finished when torrential rains again began falling and both ends of the span were inundated and torn away by raging waters of the Chickahominy.

As soon as the rains abated and while the damaged bridge was being repaired, Lowe was ordered to ascend and remain aloft to watch for any enemy movements. In a short time a message came from him reporting a large gathering of Confederate forces in the Richmond area and that some of them appeared to be moving in the direction of the Union lines.

Somewhat later, as he soared over another location, shells from 12 enemy cannon flew perilously close to his balloon, some of them actually going through his rigging, and it became obvious to him that the rebels must have previously located his base of operations in order to find the range so speedily. Under these condition he had no recourse but to descend and have the balloon taken to a point farther away from the gunfire where he could continue his observations and reports.

At noon of May 31 he sent McClellan the message that large bodies of the enemy along with trains of wagons, were moving from Richmond toward Fair Oaks. He remained aloft for several hours until he observed the rebels form a line of battle and he heard increasing sounds of cannonading.

Lowe was in the air again the next morning at daybreak and reported that the Confederates then were within four or five miles of the Union forces. Realizing that a great battle was imminent and that the balloon Washington which he had been using could not attain the altitude that he would require for necessary observations, he descended quickly and dispatched an assistant to headquarters with orders to have the larger balloon Intrepid only partially filled with gas. Another hour would be needed fully to inflate it and Lowe understood that every minute counted.

In this predicament, he climbed into the car of his Constitution which was always kept inflated but soon found that it lacked the ascension power to carry his telegraphic apparatus and an operator. What followed, is best told by Lowe himself as he related the situation afterward:

I was put to my wit's end as to how I could best save an hour's time, which was the most important and precious hour of all my experience in the army. As I saw the two armies coming nearer and nearer together, there was no time to be lost. It flashed through my mind that if I could only get the gas that was in the smaller balloon, Constitution, in the Intrepid, which was than half filled, I would save an hour's time and to us that hour's time would be worth a million dollars a minute. But how was I to rig up the proper connection between the balloons? To do this within the space of time necessary puzzled me until I glanced down and saw a 10-inch camp kettle which instantly gave me the key to the situation.

Lowe ordered the bottom cut out of this kettle so that it would serve as a wide pipe; a connection was made and the gas in the Constitution was transferred to the Intrepid.

Then with the telegraph cable and instruments, I ascended to the height desired and remained there almost constantly during the battle, keeping the wires hot with information.

|

|

|

Here is the Intrepid

being inflated from |

He finally observed reinforcements crossing the river on the newly-repaired bridge to support McClellan's troops. At length Lowe viewed the Confederates in retreat toward Richmond and realized that the battle was won by the Union forces.